materialized

Exhibit at the 2023 International Contemporary Furniture Fair /Wanted Design, May 20-23 at the Javitz Center in NYC. Booth #W875.

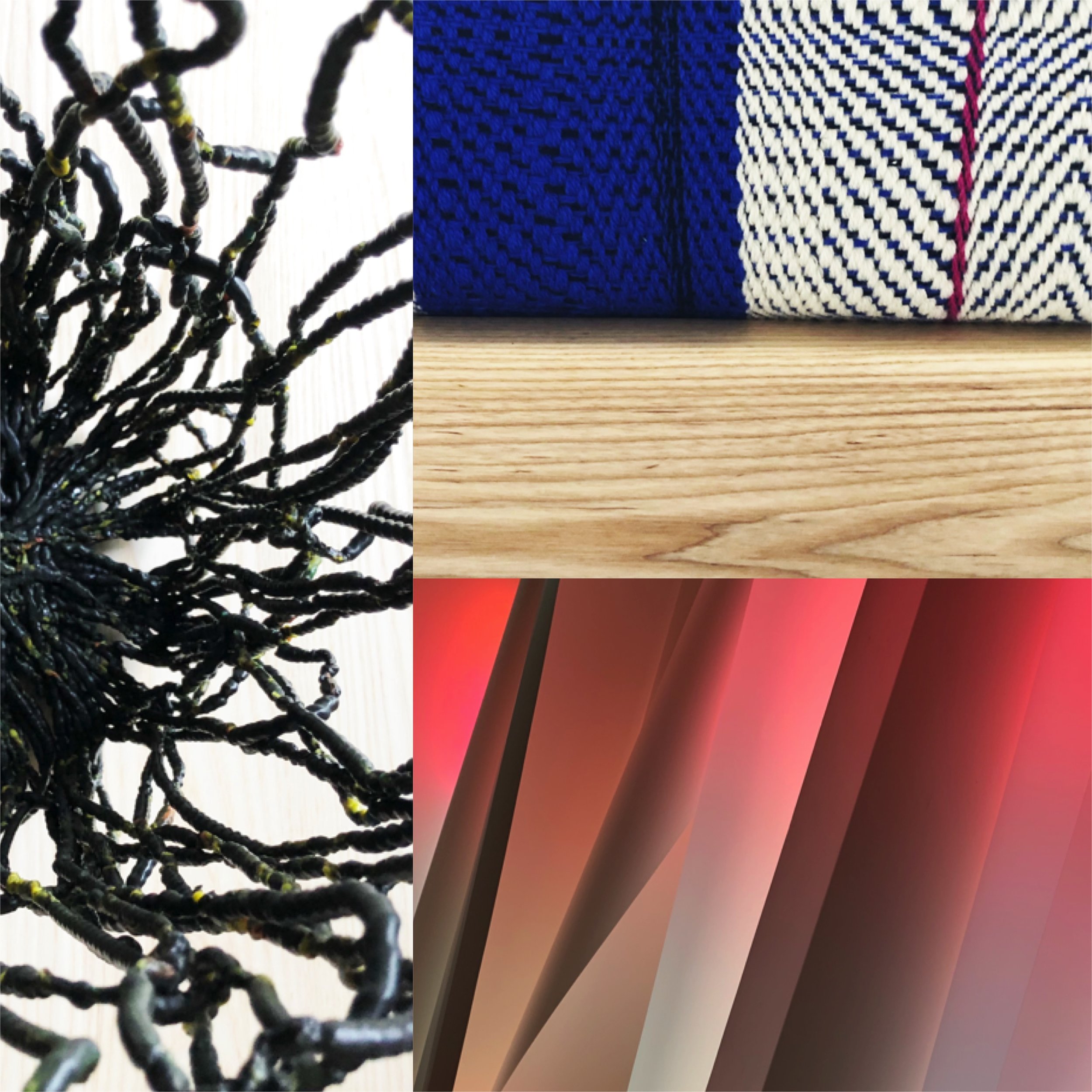

Contemporary interiors have become an eclectic mix of form languages as interior designers curate their spaces with a diverse range of objects. Mass produced products are presented in dialogue with unique craft objects and contemporary artworks. This rich mix of references has inspired furniture designers to expand the palette of material codes within interiors thereby testing the traditional lines between design, art, and craft. At Cranbrook, new methods of hands-on craft research and material investigations combine innovative semantic languages with unexpected materials, forms, textures, patterns, colors, and useful interactions. This selection of furniture and lighting objects by Cranbrook design students exaggerates the role of material experimentation in a collaged vignette to express this contemporary spatial context.

Designers: Yuyu Chen, Victor Cui, Christina Daniels, Breanne Johnson, Izzy Krompegel-Anliker, Mandy Moran, Rebecca Pedley, Andrew Riiska, Kim Swift, Phillip Tian, Nicholas Tilma

3D Designer-in-Residence, Chair: Scott Klinker

wanted design 2022

Students and projects featured in the 2022 Wanted Design International School Virtual Exhibition:

Videos in order of appearance:

99-cent Column – Madeline Isakson (3D Design ’22)

Color Value Curtains – Jenna VanFleteren (3D Design ’22)

Cushion Studies – Christina Daniels (3D Design ’23)

Divider Three – Jiangyu Wu (3D Design ’22)

Float Chair – Andrew Riiska (3D Design ’23)

Intuitive Cartographies – Eleanor Anderson (Fiber ’22), 3D Design elective

Nesting Tea Set – Yuyu Chen (3D Design ’23)

Pop-up Space One – Fabiana Chabaneix (3D Design ’22)

Soft System – Jian-Ming Lin (3D Design ’22)

Terra Wall Lights – Nicholas Tilma (3D Design ’23)

The Moonbeam – Philip Tian (3D Design ’22)

White Noise Machine – Breanne Johnson (3D Design ’23)

All videos and original music by S. Klinker, 3D Designer-in-Residence.

design mutations

Exhibit at ICFF 2019, International Contemporary Furniture Fair, Javits Center, NYC, May 19th thru 22nd, 2019. This exhibition was awarded ‘Best School’ in the annual ICFF awards.

At Cranbrook, a new generation of designers see through trans-disciplinary eyes. Old categories of design, art, and craft, interbreed to form new mutations that are comfortable in their in-betweenness. This method has been part of Cranbrook’s DNA from the start, when Mid-century designers like Eames, Saarinen, Bertoia and Knoll borrowed hands-on craft methods and contemporary art practices to revise the ‘machine aesthetic’ of the Bauhaus into a more organic, human vision of Modernism. Today, young designers find their own way to remix language and materials, like a creative science, speaking to a conceptual landscape that accepts complexity. By studying the influence of art and craft on design, the potentials of design begin to mutate and stretch into new directions that question our assumptions about use, form, materials, typology, sensory qualities, and the poetic role of objects.

Designs by Simon Anton, Joong Han Bae, Peng-Chih Chu, Dee Clements, Kyle Joseph, Karen Lee, Erik Magnuson, Cody Norman, Sunny Kim, Phoebe Kuo, Joe Parr, Joseph Shedd, Jaixiang Shen, Yi Zhang.

3D Chair, Designer-in-Residence: Scott Klinker

fine design for the end of the world

Fine Design for the End of the World is an exhibition of the 3D Design Department of Cranbrook Academy of Art at the 2016 Collective Design Fair in West Soho, New York City.

This new work by graduate 3D Design students gives voice to the hard questions that face the next generation of designers: As social, economic and environmental uncertainties threaten our modern age, does design culture now face an existential crisis? Will climate change deliver the ‘end of the world’? Will this apocalypse come by human design? Or will design somehow save the planet? With the pressing need to rethink our culture of production and consumption, can industrialized society willingly change? Can design still improve the future? Or is it already too late?

These objects do not answer all of these questions, but instead offer a poetic response - framing the problem and communicating the urgency, beauty and fragility of what is at stake.

Dialogue

Interview with Scott Klinker, Designer-in-Residence and head of the 3D Design program at Cranbrook Academy of Art. Interview questions posed by Cranbrook student Aleksandra Pollner via email.

Aleksandra Pollner: What's the intent behind the title of this show?

Scott Klinker: Fine Design, like Fine Art, is about making unique objects, not mass-produced things. Such objects can offer a critical perspective on our world, in the same manner as art. Industrial Design, in its effort to sell mass-produced stuff and be commercially ‘friendly’, almost never poses critical questions. Now is a good time in our history to ask critical questions of design, because our global systems are in crisis. All of the positive energies that went into Modernism, like utopian dreams of ‘progress’, have now found a limit—the ugly side of global capitalism: greed, social inequality, climate change, overconsumption, overpopulation. Do we just look away and keep making shiny, happy objects while the house is burning down? A rational response to that question would probably be didactic. But with this show, we offer a poetic response. Like the Memphis movement for example, this is 'design about design.'

Of course we are not ‘for’ the end of the world, which is an ironic reference. Instead we hope to point to the potential tragedy we face. It’s not about saying we’ve got the solution (precisely the kind of modernist impulse that’s now being critiqued); instead the show portrays what it feels like to face these conditions as creative young people who want to improve the world. The work can be read as a poem, a prediction, a protest or a prayer for our collective future.

AP: Who are the designers in the show?

SK: They are current students of Cranbrook’s 3D Design graduate program. Most of the students are in their 20s and come from varied backgrounds including industrial design, architecture, craft and sculpture. The group is an international mix of Americans, Asians, Europeans, men and women.

AP: How did this project come about?

SK: The project was first posed as a question to my students. I pointed to growing societal anxiety about our uncertain future, the way people work within global systems but feel they have little control over the human values that guide these systems. I asked them to think about what design means in the era of climate change, for example; given current conditions, can the motivations and ambitions of design remain the same?

The conversation evolved over two semesters, as students were encouraged to critically discuss the current state of global design in relation to global crisis. From the start the conversation was focused on a poetic response to this universal problem. We asked “what forms point to this condition?,” not “how do we fix it?”

AP: How do the students feel about growing up in an age of environmental uncertainty?

SK: How do any of us feel? We all want to improve things, but the scale of the problem is hard to comprehend. Climate change confronts all of our ‘master narratives.’ We need a new narrative, but the historical status quo is hard to redirect for numerous political reasons.

Will it lead to tragedy? Few indications point to significant change. Should we raise children in that kind of world? These are the difficult questions that every young person faces today.

AP: Is it a designer's responsibility to 'save the world' from environmental collapse?

SK: In our case, we hope to ‘save the world’ with poetic design.

All designers hope to improve the world in some way, whether it’s through new functions, forms, processes, aesthetics, etc. Design is a positive force! We hope to make the world more ‘human.’ But current conditions call human supremacy into question, and so this moment needs absolute humility, not arrogance. And this is the paradox for design: how to reimagine a role for human creativity and invention while simultaneously recognizing their limits—and even the harm they can do.

Designers, like other kinds of citizens, can ask such questions, but it takes collective will and leadership to give healthy answers. Designers have offered many visions of a more sustainable society, but very few ideas have overcome the political status quo so far.

AP: Are we already too late?

SK: Who knows? Maybe. It’s easy to imagine that the Industrial Revolution set society on a tragic course that is irreversible. Maybe that revolution was the ‘beginning of the end’ and we are simply living through the end of the world. At some point people become victims of their own comfort, shielded from nature by more and more technology until we are completely out of touch with the realities of our environment.

AP: What kind of forms came from this discussion?

SK: The formal responses to this subject were varied. Some designers responded with ‘mythic’ images of mankind, while others responded with forms derived from data. Formal themes of ‘excess’ and ‘disintegration’ were prevalent and the overall collection has a somber mood.

AP: Does 'Fine Design' have a different responsibility than Industrial Design? Can Fine Design have a critical voice that differs from Industrial Design?

Historically, Industrial Design has served industry, and therefore has reasons to be complicit with certain lies we tell ourselves about ‘progress.’ Fine Design doesn’t have these constraints. Fine Design can look more objectively and critically at design culture to ask important questions. In fact, it may be Fine Design’s duty to ask those questions that Industrial Design can’t or won’t.

Design today also operates in the world of images in addition to the physical world of ‘stuff.’ Prototypes can circulate as ideas on the internet while never being intended for production. This exhibit, for example, is intended to provoke conversation, not sell stuff.

Of course, I don’t want to sound completely uncritical of Fine Design either. It doesn’t have the same constraints as Industrial Design but that doesn’t mean it has no constraints. When we categorize our work as Fine Design we may leave behind the demands of mass production, but we are also reliant on – and need to be reflective about – the conditions that make that possible. After all, “opting out of the market” altogether is, itself, a strategy that few can afford. We need the critical distance this enables, but we can and should be critical about that privilege at the same time.

AP: What does it mean to show this kind of work at the Collective Design Fair, which could be described as an exclusive market for design ‘rarities’?

Fine Design can suffer from the same contradictions as Fine Art. It may look critically at the world, but caters to an elite audience.

We are not blind to these problems. The work is complicit with the context of elite consumption while looking at it critically. For example, luxurious materials were sometimes used to announce the object’s rarity. I don’t see this complicit/critical quality as cynical. It adds conceptual tension to the work. In the art world, it’s not uncommon for an artwork to be critical of the art scene or the art market (think of Duchamp’s Fountain). The objects in our exhibition speak to the existential contradictions of design as a whole: we all want to improve the world with new things, even as we contribute to the problems of more consumption.

AP: Why should your ideas be expressed in design objects? How does this differ from, say, sculpture?

Useful things are their own medium, and they don’t need to answer to commercial goals or even everyday functions. They have their own things to say and sometimes they do this using languages that overlap with sculpture. For example a chair is ‘figural’ and has a character like a person. It expresses these ideas before needing to perform the function of a seat. A lamp can provide ‘illumination’ both functionally and metaphorically.

• Where is the line between Art and Design?

Traditionally, Design leans more toward ‘use’ and Art toward ‘metaphor.’ But it’s time to question those lines in the sand, because as our exhibit suggests, useful things become metaphor within history whether we intend it or not. In thousands of years, an archeologist will uncover the artifacts of our society. The story these objects tell may become surprising metaphors for what is, or was, ‘human.’

innate gestures

Our interactions with objects are informed not only by acquired knowledge and comparison, but also by nuanced physical relationships with the body. Innate Gestures strives to isolate and amplify the natural sensory cues that make everyday objects intuitive, pleasurable, and simple to interact with.

13 graduate 3-D Design students explored this research in a semester-long workshop with guest designer Leon Ransmeier. The work was exhibited at the ICFF in NYC in 2009.

hands on: conceptual craft research

In the past design was solely focused on mass production, but today’s international design culture is a rich mix of design, craft, and fine art contexts in which young designers can test their ideas as one-offs, limited editions, or mass-produced products. This liberating expansion of design has inspired new kinds of hands-on craft research and material investigations combining innovative semantic languages with unexpected materials, forms, textures, patterns, colors and uses. This approach favors an analog, hands-on process of exploring form with real materials, rather than a virtual process of digital visualization. A ‘conceptual craft’ results in which the creative use of materials is valued more than conventional craft techniques, and a sensory richness is valued more than polite, modern forms. This research is shown with prototypes by 3D design students and recent alumni of Cranbrook Academy of Art. The exhibition took place at the International Contemporary Furniture Fair 2013 at the Javitz Center in NYC.

Designers:

Mark Baker, Aaron Blendowski, Jack Craig, Mark Dineen, Eric Drury, Brian Du Bois, Kristina Gerig, Seth Keller, Scott Klinker, Yukyeong Lee, Mark Moskovitz, Jonathan Muecke, Sae Jung Oh, Brittany Pool, Yating (Susan) Qiu , Christopher Schanck, Adam Shirley, John Truex, Reed Wilson

Curators:

Christopher Schanck

Scott Klinker, Cranbrook 3D Designer-in-Residence

cranbrook for alessi

This exhibition featured prototypes created in a collaborative workshop initiated by Alessi, the Italian ‘design factory’ with Cranbrook Academy of Art. The 2009 workshop was a mix of Cranbrook crafts people and designer/makers working together in the metal shop for a week of open-ended material investigations to explore metal forms and techniques. The prototypes shown in the exhibition are a mixture of material studies, product proposals and pre-production samples delivered by the workshop to demonstrate the mix of hands-on craft methods and design methods that drove the process. Four new Cranbrook designs were approved for production and launched in 2012.

The workshop was co-directed by Cranbrook 3-D Designer-in-Residence, Scott Klinker and Metals Artist-in-Residence, Iris Eichenberg. Participants from the Metals program included Adam Shirley, Seth Papac, Katie MacDonald, David Schafer, Richard Nelipovich and Suzanne Beautyman. Participants from the 3-D Design program included John Truex, Patrick Gavin and Jonathan Muecke.

rest and concentration with herman miller

Rest and Concentration in the Workplace

Enabled by wireless tablets and smart phones, today’s offices have adapted to the fluid interactions needed for teamwork, yet rarely provide space for private rest, concentration or ‘personal time’. When individual workers need a moment away from the group, what new furniture types will support their rest and concentration? If new work cultures require an integration of living and working, then what is the new vision of physical rest in a professional setting?

16 Cranbrook design students explored these questions as research for Herman Miller International. Six proposals were chosen for prototyping and shown at ICFF in NYC, 2012.

Department of 3D Design 2012:

Vladimir Anokhin, Jack Craig, Mark Dineen, Eric Drury, Brenton Elledge, Kyle Fleet, Mike Haley, Da Mee Hong, Douglas Leckie, Yukyeong Lee, Elizabeth Moran, Cana Ozgur, Christopher Palmer, Ryan Pieper, Matthew Plumstead, Tristan Roland

Cranbrook Project Lead:

Scott Klinker, 3D Designer-in-Residence

Herman Miller Project Lead:

Gary Smith, Director, Design Facilitation & Exploration

student work archive

This selection of student projects from 2001 to the present shows the wide range of research explored at Cranbrook 3D Design. Since 2001 , nearly 150 students have graduated from 3D.

No singular style or methodology has defined this era. Instead, the program investigates the broad connections between ideas and forms. Rigorous analysis of these connections then informs our decisions in ‘giving form.’ This wide framework allows a designer to develop an authentic creative ‘voice’ that can communicate with a clarity of intent. Our educational model has allowed many points of entry - testing the boundaries of design with experiments in new materials and processes, new behaviors, new interactions, new cultural codes and new spatial codes.

featured alums: fine design

To fit the changes in design culture since 2000, 3D at Cranbrook has addressed two distinct contexts: Industrial Design and Fine Design. Fine Design, like Fine Art, is about making unique objects, not mass produced products. This work, also known as ‘collectible design’, usually circulates through specialized design galleries that sell to collectors and sometimes to interior designers seeking signature objects for special projects. This work is known for testing the lines between design, art, and craft - emphasizing concepts, techniques, and materials not commonly found in ‘mass’ objects. This kind of practice has a lineage to the tradition of ‘studio furniture’ where skilled craftsmen would ‘author’ unique pieces, like the practices of George Nakashima or Sam Maloof working in wood. Today’s studio furniture goes beyond these traditions by inserting radically new techniques, materials, and abstract languages.

Cranbrook 3D has built relationships with renowned design galleries on the scene with an increasing number of graduates finding the gallery representation and support needed to build their careers. Curators from major galleries regularly attend our annual Degree Show to scout for new talent.

featured alums: industrial design

To fit the changes in design culture since 2000, 3D at Cranbrook has addressed two distinct contexts: Industrial Design and Fine Design. Industrial Design may be considered the more traditional approach, with an emphasis on mass production. Designing within the constraints of a ‘mass’ context is an art in its own right. Cranbrook designers are known for their artful approach to form, bringing new stories, techniques, sensory qualities and formal refinements to mass production.

Alums of the program have explored several models of practice.

• in-house designers practice within design-driven corporations. Nike, for example, has hired 7 recent 3D grads, and has an on-going recruiting effort at Cranbrook.

• independent consultants to industry sell their time and expertise or license their designs to manufacturers.

• self-producers take a more entrepreneurial approach and produce their designs on their own, either through sourcing the products with vendors or overseeing production in their own shops. Several 3D alums have started their own companies making their designs, often in small batches and distributed directly to customers via online e-commerce. This new model is sometimes described as ‘D2C’ or designer-to-consumer.

Cranbrook’s network of alums serves as a vital resource to connect our graduates with the opportunities to begin a career path.